Classification : Combination Syndrome

Classification of Combination Syndrome

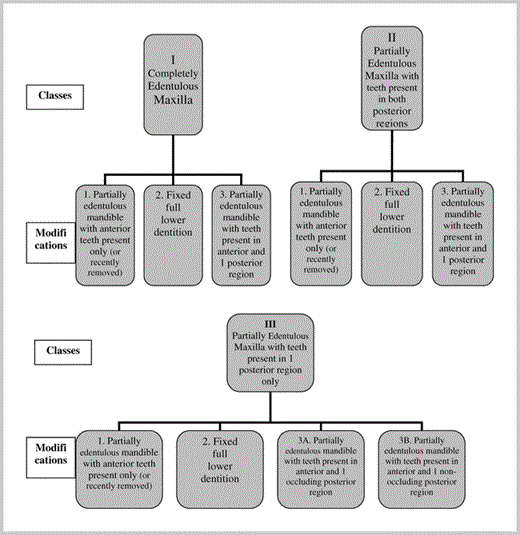

Kelly was the first person to use the term “combination syndrome.”5 He believed that the key to many symptoms of the combination syndrome is the “early loss of bone from the anterior part of the maxillary jaw.”3 The other consistent features of this dental condition include enlargement of maxillary tuberosities and mandibular posterior bone resorption that can be present in many but not all CS cases. Based on a literature review and the author's experience with a variety of combination syndrome patients (complete and partial maxillary and mandibular edentulous cases), a clinically relevant classification of combination syndrome is proposed. Three classes and 10 modifications of CS are described below. An anterior maxillary resorption resulting from the force of anterior mandibular teeth is the key feature of this classification, and it is consistently present throughout all classes and all modifications. “Maxillary edentulous condition” defines the class, “mandibular” the modification within the class. A treatment for each category of patients with CS is suggested (Figures 18 and 19, Table).

-

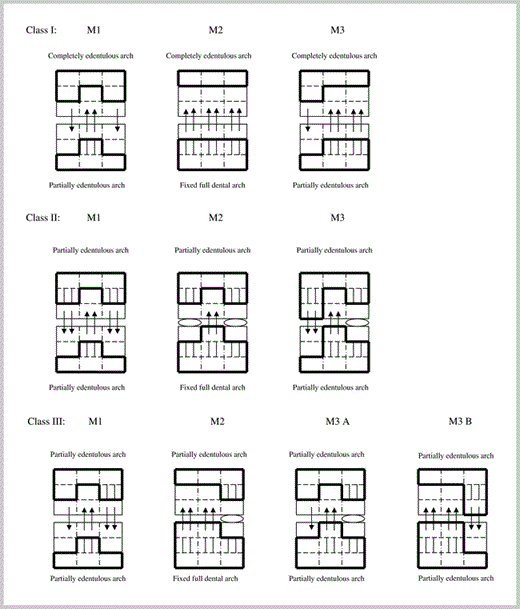

Class I: Maxilla: completely edentulous alveolar ridge. Mandible: Modification 1 (M1): partially edentulous ridge with preserved anterior teeth only. Modification 2 (M2): stable “fixed” full dentition (natural teeth or implant-supported crowns/bridges). Modification 3 (M3): partially edentulous ridge with preserved teeth in anterior and one posterior region.

-

Class II: Maxilla: partially edentulous alveolar ridge with teeth present in both posterior regions, edentulous and atrophic anterior region. Mandible: modifications are the same as in Class I (M1, M2, and M3).

-

Class III: Maxilla: partially edentulous alveolar ridge with teeth present in one posterior region only, edentulous and atrophic anterior and one posterior region.Mandible: modifications are consistent with Class I and II (M1, M2, M3A, and M3B) (Figure 18).

This classification is based on what seems to be the dominant feature of most CS cases—an edentulous premaxilla with an advanced resorption of anterior maxillary bone and overgrowth of the anterior mandibular bone with extrusion (super-eruption) of lower front teeth.

According to this classification, the patient in the presented case report (Figures 6 through 10) had Class II, Mod. 2 (II-2): a partially edentulous maxilla with the posterior teeth present bilaterally opposed by the full fixed (crown and bridge) dentition. The typical (and the most commonly observed in the dental practice) case of CS exemplified at the beginning of this article and in Figures 1 through 3 would be Class I, Mod. 1 (I-1): a completely edentulous maxilla opposed by the partially edentulous mandible with preserved anterior teeth only. Similar cases can also be observed with a fully edentulous maxilla and mandible where the anterior mandibular teeth have been recently removed. The damage from these teeth that caused typical signs and symptoms of the CS still remains. That is why these cases belong to the same classification category of Class I, Mod. 1 (I-1). The partial edentulous case depicted in the Figures 4 and 5 would be Class II, Mod. 3 (II-3): a partially edentulous maxilla with the posterior teeth present bilaterally opposed by the partially edentulous mandible with teeth present in anterior and one posterior region. In general, an extraction of teeth that initiated the specific pattern of the CS does not change the class and modification within the class. The classification would remain the same, as if these teeth that are responsible for the CS jaws and teeth abnormalities were present.

An important consideration of this CS classification is the fact that a slow remodeling of bone with tendencies towards atrophy or hypertrophy (overgrowth) depends on unfavorable pairing of healthy teeth (or implant-supported bridge) in one jaw opposed by an edentulous region in the other jaw. A persistent occlusal pressure of solid teeth on the edentulous opposing alveolar ridge over time will cause a bone atrophy of the edentulous region. A reverse effect of hypertrophy of the alveolar bone with an extrusion of teeth opposed by an edentulous jaw segment is also evident and usually develops synchronously. A pairing of healthy maxillary and mandibular teeth in a stable occlusion in any dental region can usually show little or no bone changes or teeth extrusion due to opposing forces that tend to cancel each other and maintain an occlusal balance (Figure 19). The forces of occlusal pressure causing bone remodeling towards atrophy or hypertrophy can cause mild, moderate, or severe changes. This depends on many factors, including presence or absence of teeth, history of tooth loss (trauma or extraction), periodontal condition of present teeth, history of edentulism and prosthetic treatment (removable or fixed, denture quality), an implant treatment (if done)—immediate or delayed, density of bone in the region, presence of parafunctional habits (bruxism), muscular facial biotype (brachycephalic), jaw relationship, type of occlusion, dietary habits, and other factors.

Serial posts:

- Combination Syndrome: Classification and Case Report

- Introduction: Combination Syndrome

- Case report: combination syndrome

- Diagnosis: Combination Syndrome

- Treatment Plan : Combination Syndrome

- Operative phase : Combination Syndrome

- Restorative stage : Combination Syndrome

- Classification : Combination Syndrome

- Discussion : Combination Syndrome

- Conclusion : Combination Syndrome

- References : Combination Syndrome

- Table Classification of combination syndrome (CS)

- Extended table of classification of Combination Syndrome (CS)